Share

Written by

Feature Image

Clarence Comyn Taylor / British Library

Clarence Comyn Taylor / British Library

The study of history merits a different answer. There was little fear of British military intervention in Nepal from the moment the British acquired its newly conquered territories of Kumaon, Garhwal and parts of Sikkim after the Anglo-Gorkha war; the difficulties of a military expedition in the hills of Nepal were clear to the British. A three-decade period of what historians have called “peace without cordiality” followed, but with the advent of the Ranas, Kathmandu’s disposition towards the British noticeably changed from adversarial to acquiescent. The British had initially hoped to profit from the trade in Nepal. But subsequent to the war, and the Rana policy of appeasement, it did not need to intervene militarily to secure that either.

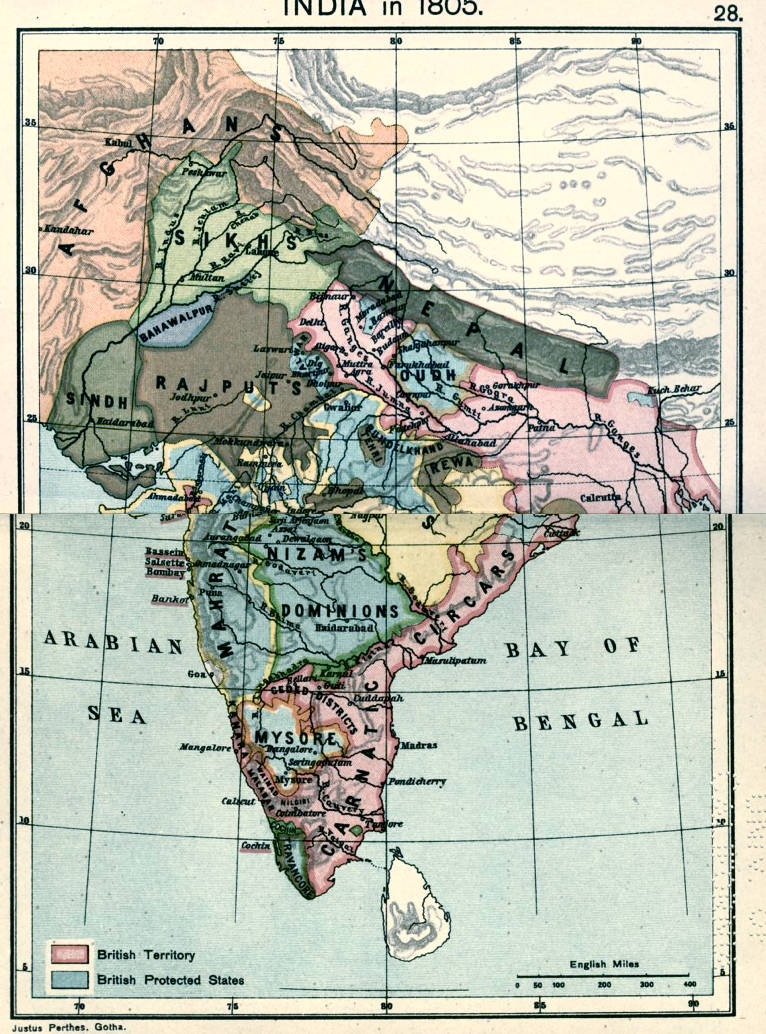

In examining why the British never colonized Nepal, it is imperative to first clarify the nature of British rule in the subcontinent, and how it varied from preexisting state formations like that of the Gorkhas. What we today call the “British Raj” in the subcontinent consisted of two different territories: areas that were directly governed by the British, such as the province of Bengal; and princely states under British paramountcy, like in the Rajputana region of today’s Rajasthan, which accepted British suzerainty but continued to be ruled by native rulers.

Map of British India in 1805, from A Historical Atlas of India for the use of High-Schools, Colleges, and Private Students, Joppen, Charles [SJ.] (1907). Photo credit: Fowler&fowler / Wikipedia

In British political thought, however, a boundary was a static idea, well-defined by border pillars, surveys, and other accoutrements that continue into the modern era. In an exchange of correspondence between the governor general in Calcutta, the Resident Edward Gardner in Kathmandu, and the Nepali court in July 1816 after the Sugauli Treaty, when negotiations to return a part of the Nepali Terai began, the British insistence on clear demarcation of the border is evident. On instructions from Calcutta, Resident Gardner wrote to the Nepali court, “A new border would be established about four miles south of these northern points on the old border…The actual line cannot be settled without surveys, but wherever it is placed, it must prevent future disputes and be clearly defined.”

The British emphasis on the fixity of a political boundary was one of the reasons they went to war with the Gorkhas in 1814. Even before things took a turn for the worse in 1814, the British were perplexed by the lax definitions of a boundary that existed in the region. As far back as 1795 itself, EIC Governor General Lord Cornwallis had assured the Gorkhas he was willing to “define the long-uncertain border between the Morang and the district of Purnea”; in the areas around Awadh and in the Gorkha territories of Kumaon and Garhwal, the boundary had “been made so uncertain” that the British were “perplexed as to how to react” when the Gorkhas moved into new territories. Historian John Pemble quotes the curious example of the Bareilly magistrate who, in 1811, noticed the Gorkhalis had built a fort in Kheri—which didn’t exist till two years prior. “Such is the undefined boundary between the two governments,” the magistrate wrote.

Farther west, towards the foothills of the newly conquered Sutlej-Garhwal region, General Ochterlony, on behalf of the governor general, offered Nepal the ‘Principle of Limitation’ in 1810. He informed Amar Singh Thapa, commander of Gorkha forces in the region, that the Gorkhalis should stick to the hills, which the British had no interest in: “all territory below the line of the foothills, whether previously attached to hill states or not, were now under the protection of the Company.” But Ochterlony was, as Pemble suggests, “itching for a fight,” and in 1813, when the Gorkhas seized six villages that were supposedly in the lowlands, he began making preparations for a military expedition that would expel the Gorkhas “from all hill areas west of the Ganges.” Amar Singh Thapa, who was hesitant to meet the British in open confrontation, asked for time to consult Kathmandu; its response was based on a sole factor: who conquered the areas first? Thapa suggested to Ochterlony that the Gorkhas and the Company could share the contested territory, but that was anathema to the half-American, half-Scot military commander. Pemble writes:

Ochterlony’s

refusal to respond to Amar Singh’s overtures made the Kaji feel

humiliated, and his aversion to the British deepened; but he knew better

than to goad them beyond a certain point…Others of his race were not so

circumspect, and in negotiations over disputed borders further east

words and actions of uncontrolled impetuosity led to the collapse of

negotiations and the declaration of war.

The disputes further east

Pemble refers to occurred in the tracts of Butwal and Makawanpur.

Butwal—held by the Palpa kingdom as a tenant of the Nawab of Awadh—was

incorporated into the Gorkha empire in 1804. The British, who by then

controlled Awadh, insisted the Gorkhas withdraw from the villages, but

to no avail. This dispute remained on the sidelines until 1811, when

another boundary dispute occurred in Makwanpur. The Gorkhas had occupied

villages that they claimed were part of the Makwanpur hill state. But

the Raja of Bettiah—who paid tribute to the Company—insisted the

villages came under his dominion, as he paid rent for them, and sent an

armed contingent to wrest them back. When a Gorkha subba was

killed in the ensuing confrontation, Calcutta proposed an Anglo-Gorkha

commission to look into disputes in both Makwanpur and the Butwal area.

With both tracts lying in the fertile Terai region, Kathmandu was

reluctant to give them up, and when its representatives asked for time

to consult on the matter, the Company’s representative, Major Paris

Bradshaw, announced the documentary evidence they had produced was

enough to establish the rights of the Company in the occupied

territories.

“Assemblage of Ghoorkas,” a coloured aquatint made by Robert Havell and Son, based on James Baillie Fraser’s Views in the Himala Mountains. Fraser’s brother William was a political agent during the Anglo-Gorkha War. Photo credit: British Library

War was now inevitable. The Marquess of Hastings—a “hawk” by modern military standards—had decided that military aggression against the Gorkhas would, apart from resolving the disputes, also signal to the other princely states of the subcontinent that Company authority in the region would be “de-facto” from hereon.

:::::

The

war brought severe losses to the Gorkhalis. Almost a third of Gorkha

territory was lost to the British, including the key territories of

Kumaon and Sikkim. The British had long insisted Gorkha authorities

allow them to trade through their territories onwards to Tibet, but

Kathmandu had been adamant about not allowing the firanghis in

their country. All trade with Tibet, they insisted, “be confined to

channels through Nepal.” With the control of Kumaon and Sikkim, the

Company no longer had to rely on the Gorkhas to trade with Tibet. At any

rate, as Pemble argues, by 1814, the trade with Tibet would bring

little in value to the Company. If trade with China was a concern, the

port of Canton was already open to the Company’s ships. Further, the

Company had realised, through Maulvi Abdul Qadir’s 1795 Nepal expedition,

that Nepali traders were essentially middlemen between Tibet and Indian

merchants, and that direct trade with Tibet and China would be “highly

beneficial” to the Company’s interests. Kirkpatrick’s 1792 mission had

already made it clear that the fabled gold of Nepal was actually Tibetan

in origin, and Nepal itself didn’t have any gold mines.Nonetheless, whether the motives behind the war were boundary disputes, trade issues, or a simple itch by the Company to assert its might in the region is of little significance. War seemed to be inevitable between the two powers in the north the moment Gorkha troops came into conflict with Company troops over issues of territorial demarcation.

The war reshaped the political boundaries of Nepal, and hemmed it in on three sides with Company forces. If the loss of territory wasn’t sufficient reason for Bhimsen Thapa to be convinced that the Company had the firepower to overrun Kathmandu, Ochterlony’s punitive and lightening-quick expedition to Makwanpur in February 1816, when Kathmandu delayed the ratification of the Sugauli treaty, would have conveyed to Thapa the extent of British military might. The treaty also formalised the political boundary between Nepal and British India, and few disputes were to occur in the years to come on this issue. As Stiller writes, Thapa’s commitment to the fixed border was “total”: “Thapa realized that the best way to insure Nepal’s continued freedom from interference was to grant the governor general’s basic desire, a secure and trouble-free border.”

The subsequent three decades saw a period of “peace without cordiality,” where the British resident in Kathmandu was increasingly pitted against the bharadars, with political intrigue being the order of the day. A section of the Kathmandu court continued to insist on challenging the British militarily and demand a return of the erstwhile territories. But Thapa managed to keep them at bay till the end of his premiership. Another section of the court believed the British to be able allies, and solicited their support to further their own agendas. The residents were instructed to keep a close eye on British interests in the country, and they became part of the intrigue that marked this period in Kathmandu. In June 1840, “an army mutiny over proposed pay reductions almost turned into an attack on the Residency because the soldiers were led to believe that the cuts had been forced on the Nepalese government by the British,” according to historian John Whelpton. But this was by far the most serious transgression during this period.

“A Nepalese Official (Perhaps Prime Minister Bhimsen Thapa, served 1806-1837)”, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).

Such intransigence would not be suffered either by Kathmandu or by Calcutta, and the new governor general, Lord Ellenborough. The governor general had decided against a policy of allying British interests with those of certain ministers in the Kathmandu durbar who were in “constant fear about their own personal safety.” And those who could not prevent embarrassing episodes like the Kasinath affair from happening could not “guarantee British security” either. Hodgson would be relieved of the Residency in 1843, and Whelpton argues, correctly, that “despite Hodgson’s success in gaining widespread support among the bharadari…it would probably have been better for Anglo-Nepalese relations if the [EIC] had…confined itself to demanding a change of policy, and not concerned itself with the identity of the king’s counsellors.”

Hodgson’s attempts to play one section of the bharadari against another after the fall of Bhimsen Thapa won him few friends in the tense political atmosphere of the time, especially in a court that was used to political intrigues since its beginnings. One can argue that the Residency support did little to undermine the section of the court which insisted on a military confrontation with the British to regain the lost territories. It was only Thapa’s near-total political control that kept the warmongers at bay. It must be remembered that the flux that marked Jung Bahadur’s ascendancy began only after Thapa was removed from his post, imprisoned, and forced to commit suicide. It was also during this period of flux that Anglo-Nepal relations were at their nadir after the war.

:::::

On

April 16, 1853, 400 people got onto 14 carriages pulled by three steam

locomotives from Bombay to Thane—the first passenger train journey in

India. The Times of India reported:

“The 16th of April 1853 was, and would long continue to be one of the

most memorable days, if not the most memorable day, in the annals of

British India.” Little did the old lady of Boribunder know that the

train journey would be momentous not just for India but for the fortunes

of the Ranas in Nepal too.The Kot Massacre had brought the Ranas to power, a transition that historian Mahesh Chandra Regmi has called the beginnings of a “centralized agrarian bureaucracy.” The Rana period was marked by a dedicated commitment to extract as much revenue as possible from Nepal’s resources—land or otherwise. The administration subsequently developed an intricate network of local authorities who were primarily revenue officers across the state, and indebted to the Ranas for their positions. After the introduction of railways in India, the British began to develop an infrastructural network across northern India to support industrial development. The demand for timber—to be used as railway sleepers, railroad ties, planks for bridges, or for use in homes—was growing exponentially. Jung Bahadur, sensing a change in the winds, banned all logging operations in the eastern Tarai—around Morang—in 1855. As most of north India’s sal forests had been depleted by then, “the major sources of supply were, consequently, left on the Nepali side of the Tarai border.” A restricted supply of timber resulted in a sharp increase in their prices, with prices in 1860 three times what it was three years prior, according to the magistrate in Champaran.

Watercolor of the British Residency at Kathmandu in Nepal, by Henry Ambrose Oldfield, c. 1850. Photo credit: British Library

Timber export to India was important enough for the Ranas to invest in new, industrialized methods, such as saw mills that would produce and export railway ties from Nepal itself. Saw mills were set up in Nepalgunj and Nawalpur in 1900-01 under Bir Shumsher, the first time in Nepali history that the government had invested in mechanical capital to boost industrial production. Although the government made way for private contractors in the trade, Nepali sal remained one of the most sought-after sources for ties and sleepers for the expanding Indian railway network.

Much of this trade was conducted via the newly inducted territories of Naya Muluk— consisting of the modern-day districts of Kailali, Banke, Bardiya and Kanchanpur—which were returned to Nepal in the aftermath of Jung Bahadur’s military assistance to the British in the 1857 Rebellion, along with “the whole of the lowlands lying between the river Rapti and the district of Goruckpore”. An 1897 report concluded, “The great marts of Nepal on the border of Oudh are Golamandi and Banki, alias Nepalgunj… The policy of the Nepal Durbar is to force all hill produce to be brought to these places.”

The century-long Rana rule saw an overhaul of Nepal’s relationship with the British, which, by all accounts, transformed from one of reluctant peace to an alliance. One reason for such a change in outlook was the Rana family’s relative outsider status in the Kathmandu durbar, and their overtures to the British were obviously meant to keep the other bharadar families at bay. Calcutta, which wasn’t initially enamoured by the bloody way through which Jung Bahadur and his family had gained power, found itself being seconded to London, for whom Jung Bahadur’s military assistance in the siege of Lucknow, and his 1850 visit to the European continent, had been sufficient to raise him to the ranks of Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Bath in 1858. Jung Bahadur’s efforts in the rebellion were significant enough that they were “unwilling to imagine the position in which we should now have been without this aid from the Maharajah,” as a note to Lord Canning authorizing the return of the territory said.

Jung Bahadur, a most astute military man by most accounts, was convinced that no Indian state could hope to defeat the British in open warfare. Yet, his support to them was predicated on the belief that they would honour their obligations towards a friendly government in Nepal, which had offered them the full use of its military services during a testing time for the Empire. The waning of China as an imperial power subsequent to the Taiping Rebellion was another reason why the Ranas began to look southwards. But their affinity to the British was also strengthened by Jung Bahadur’s conviction—formed after his visit to Europe—that “collaboration [with the British] was the surest means of securing advantage in the short term and of postponing the absorption of Nepal in the British Empire, a probability in the long run,” as Whelpton argues. With such a turnaround in policy, the animosity that marked Anglo-Nepal relations dissipated under the Ranas. Hunting expeditions for various royal figures and important personnel from the Raj in subsequent years gave them a forum to discuss matters beyond the sharp eyes of Kathmandu.

Prince

Albert and his suites with Bir Shumsher at a hunting trip in Nepal’s

Terai during the prince’s 1889-90 visit to India and Nepal. Photo

credit: Madan Puraskar Pustakalaya

There were hiccups, though. Even as London acknowledged Jung Bahadur’s, and Nepal’s, contribution to quelling the 1857 rebellion with the return of land, monetary grants, and the Knight Grand Cross title, Jung Bahadur wasn’t satisfied. Despite all that he had done, Britain would not acknowledge Nepal’s independence. He was particularly peeved by not being consulted over the return of the land—which, he thought, was rightfully Nepal’s in any case—and expected more territory. Calcutta too belittled him; Jung Bahadur found that he had been awarded the Knight Grand Cross title from newspapers, and not officially via Calcutta.

British resistance to acknowledging Nepal’s independence may have had to do with the Raj’s own peculiar nature. In Rajputana, although the Rajput states insisted (some till this day) that they remained independent, they were all but vassal states of the Raj, with foreign policy and defence being determined by the British. Calcutta may have expected a similar relationship with Nepal as it had with Sikkim or Bhutan, but Nepal’s politicians were far wilier, and the idea of nationhood far more entrenched. British attitude towards Nepal at this time may be surmised through Resident E L Durand’s letters in 1889. Asking for a change in British outlook towards Nepal, he wrote that Calcutta should emphasise on Kathmandu “the fact of the supremacy of the British Government… the fact of the absolute dependence of Nepal upon the generosity and liberality of Government [of India], and the fact that no outside claims or interference with our undoubted protectorate [emphasis mine] could be tolerated in regard to any State on this side of the Himalaya.” Ten years previously, Durand’s brother Henry Mortimer—who devised the Durand Line separating Afghanistan and British India which today is the Afghanistan-Pakistan border—as foreign secretary wrote, “Nepal is not absolutely independent…but practically we have treated her as an independent State, having power to declare war and make treaties.”

Another British diplomat, Lee Warner, remarked, “I have never regarded Nepal as ‘independent’ except in certain attributes of sovereignty. Its internal sovereignty is more complete than that of any other protected state of India. But it has no real international life… It is, therefore, in my opinion a glorified member of the protectorate.” But the final word on British perception of Nepali sovereignty came from the Viceroy Lord Curzon himself. In a 1903 letter to the Secretary of State, Curzon wrote, “It approximates more closely to our connection with Bhutan than with any other native state… Nepal should be regarded as falling under our exclusive political influence and control.”

Although Britain never exclusively suggested Nepal had a similar status as the other princely states under its protectorate, it did not agree on whether Nepal was fully independent either. This ambiguity allowed it to discourage Nepal from establishing relations with other foreign powers, and weaken Nepali claim to “unrestricted acquisition of arms and machinery,” as Mojumdar writes.

Nepal had sought modern arms from Britain in view of its deteriorating relationship with Tibet. The two countries had fought a war in 1855-56, and with trade no longer as pertinent to the relationship as earlier, relationships between the two had grown tense. In 1883, Nepal asked Britain to provide it with modern guns if war broke out between the two countries. Foreign secretary Durand was not in favour of interfering in the event of a war, but if Nepal did invade Tibet, he suggested that “as an exchange for the arms the Government of Nepal must allow freer recruitment of Gurkhas for the British Army and a definite arrangement should be provided for before arms are sent.” The British were also closely watching Tibet, where Russia was attempting to spread its influence.

The military recruitment of Nepali men into the British army had been reluctantly agreed to by Jung Bahadur, albeit with stringent rules, after the rebellion. When the British asked Ranoddip Shumsher, Jung’s successor, for 1,000 troops in 1878, Ranoddip sent half the number, of whom not many were fit for service. But this would change under the rule of Chandra Shumsher, who used Gurkha recruitment as a quid pro quo to acquire arms from the British, and eventually, to recognise Nepal’s independence. The first batch of arms and ammunition was supplied in 1904, nearly 20 years after Nepal first requested Calcutta. Between 1906-08, 12,500 rifles were supplied to Chandra Shumsher. Similarly, between 1901-1913, 24,469 Nepali men were recruited into the Gurkha regiments.

Gurkhas

preparing meal on July 23, 1915, in St Floris, France, during the First

World War. Photo credit: H. D. Girdwood / British Museum

“Few who have met Maharaja Chandra will ever forget the geniality of his smile and conversation,” historian Perceval Landon wrote of him in his hagiographic account Nepal, for which Chandra reportedly paid Landon INR 165,000. Short, with a piercing set of eyes, Chandra, according to Landon, displayed the same “foresight and tenacity of purpose” as Jung Bahadur. Like his uncle, he too veered Nepal’s foreign policy towards the British, displaying an affinity far closer than any other Rana prime minister. Any pretensions by the British that Nepal was a vassal state of China were removed by Chandra in a most forceful way: “The claim—that the deputation [to China; Nepal had agreed to send a deputation to China every five years in a 1792 treaty] proved the vassal character of Nepal—is not only an unwarranted fiction but is also a damaging reflection of our national honour and independence.”

A year before the Younghusband expedition, Chandra met Curzon at the Coronation Durbar, a ten-minute meeting that stretched to an hour-and-a-half. A few days after the meeting, Curzon wrote:

We

believe that the policy of frank discussion and co-operation with the

Nepalese Durbar would find them prepared most cordially to assist our

plans [in Tibet]. Not the slightest anxiety has been evinced at our

recent forward operations on the Sikkim frontier; and we think that,

with judicious management, useful assistance may confidently be expected

from the side of Nepal…the Maharaja is prepared to co-operate with the

Government of India in whatever way may be thought most desirable.

Chandra’s

acquiescence to the Raj continued well into the first World War, when

Nepal loaned India ten battalions, and eased Gurkha recruitment. It is

well-known that nearly 55,000 Nepali men fought in the war—from

Gallipolli to France, and with the Lawrence of Arabia. Such generous

demonstration of friendship was expected to bring its own reward.

Although Chandra was expecting more than the annual monetary gift of Rs.

1 million, the British decision to change the designation of the

Resident to Envoy, and the Residency to Legation, marked the first steps

towards absolute Nepali ‘independence’. As The Times (London) reported

on 4 June, 1920, “This decision is intended to emphasize the

unrestricted independence of the Kingdom of the Gurkhas, which is on an

entirely different footing from that of the Protected States of India.”Three years later, the Nepal-British Treaty reinforced Nepal’s status, with the first clause being “Nepal and Britain will forever maintain peace and mutual friendship and respect each other’s internal and external independence.” This treaty would also be the basis for the 1950 Treaty of Peace and Friendship signed between an independent India and Nepal. Although the former still implied Nepal could only import arms from India, Nepal’s independence had finally been achieved. One minor hiccup would be faced when Nepal applied to the United Nations’ membership in 1949, when Russia vetoed the application questioning its “sovereign status.” By 1955, that hurdle too had been overcome.

:::::

With

the advantage of retrospect, one can argue that Nepal’s sovereignty was

closely tied in with its relationship with the British. Until the

advent of the Ranas, there is no indication that the British thought of

Nepal as any different than the other princely states of the

subcontinent. Although Nepal was not a protectorate, it wasn’t regarded

as an independent sovereign state by any right, as the comments by

high-ranking British diplomats suggest. Indeed, the 1816 Sugauli treaty

was signed not with the kingdom of Nepal, but between the “Honourable

East India Company and the Rajah of Nipal [sic].” It was the “Rajah” who

ceded the territories after the war, not the country. Even as late as

1860, the treaty was between the British government and “the Maharajah

of Nepal,” and it was to the Maharajah that the lands were returned.The marked improvement in ties between Calcutta and Kathmandu came under Jung Bahadur, who didn’t let existing disappointments trouble his relationship with the Crown. Ties were extended via the massive shikar expeditions, with Prince Albert Edward, the heir to the British throne, arriving in 1876. Further, there was the carrot of military recruitment. The significant contribution that “Gurkha” recruitment into the British Army made to Nepali independence have rarely been touched upon. Were it not for the quid pro quo as demanded by Chandra Shumsher on the completion of the First World War, the treaty ratifying Nepal’s total sovereignty would not have come about. Chandra’s offer of Nepali troops and vast numbers of Nepali men had the desired effect on the British Crown’s perception of Nepal as a friendly “native” state, and hence to be adequately rewarded. Political scientist Leo Rose goes as far as to suggest “Jang Bahadur and Chandra Shumsher deserve recognition as two of the great nationalist heroes of Nepal.”

Such statements are not without their detractors. For one, Rana foreign policy was motivated by a survival instinct: in the dangerous corridors of Kathmandu politics, where the Ranas were relative newcomers to the upper echelons of the government, only the British as outsiders to Kathmandu’s politics could be trusted. The Rana prime ministers often could not trust their own relatives, as Ranoddip found out to his detriment. Furthermore, Rana rule was closely tied to the fortunes of the Raj till the end. The colonial aspect of British rule had a perfect ally in the extractive feudal nature of Rana rule, and the former’s withdrawal from India laid the grounds for the latter’s eventual collapse in Nepal.

Nepal’s

last Rana prime minister Mohan Shumsher with foreign delegates, during

the inauguration of Juddha Shumsher’s statue, on the day of Bhoto Jatra,

1948. Photo credit: Madan Puraskar Pustakalaya

Unfortunately for the Ranas, increased Nepali participation in Raj military expeditions slowly weakened the foundations of their rule. More than 200,000 Nepali men participated in the Second World War on various fronts, at a time when the call for total independence in the subcontinent had reached far and wide. The rise in political consciousness amid a growing nationalist movement in India came to haunt the Ranas, whose control was dependent on keeping Nepal insulated from such developments. The opening up of Gurkha recruitment—intended to provide an avenue for employment, as the Ranas barely initiated any economic development in the hills where the men were drawn from—also compounded the increasing migration of Nepalis into India, as Gurkha recruitment had, as is now, better pay and amenities than the state army.

So why did the British Empire never colonize Nepal? A reductive answer would be: because it simply did not feel the need to do so. The Anglo-Gorkha war had secured it a territorial advantage vis-à-vis any trade expeditions to Tibet; the subsequent friendly Rana regime had provided it with the benefits of a secure border across a significant part of its territory; the ruling dynasty’s economic and political fortunes were closely tied in with the Raj; and the British had access to the best of Nepali resources—men and natural resources—without the need to deal with administration or the pains of dissent. Its political influence over the kingdom was complete; Rana isolation of Nepal was compounded by the British restricting its external contact. British recognition of Nepali “independence” brought little change in the relationship between the two. The British had tactfully addressed Nepali pride and sensitivity about its sovereignty, while Nepal remained within British India’s political framework and its external relations were adjusted to “requirements of British policy”. The “independence” of the Nepali state in the age of empires was thus secured via a complex terrain of political negotiations and domestic alliances, foreign-policy course corrections, and the sacrifices of thousands of Nepali men who fought for the Empire.

:::::

Further reading:John Pemple, The Invasion of Nepal: John Company at War (Clarendon Press: 1971)

Ludwig Stiller, The Silent Cry: The People of Nepal 1816-1839 (Sahayogi Prakashan: 1976)

Stiller, Nepal: Growth of a Nation (HRD Center: 1993)

K.C. Chaudhuri, Anglo-Nepalese Relations: From the earliest times of British rule in India till the Gurkha War (Modern Book Agency: 1960)

John Whelpton, Kings, Soldiers and Priests: Nepalese Politics 1830-57 (Manohar Publications: 1991)

Mahesh Chandra Regmi, An Economic History of Nepal 1846-1901 (Nath Publishing House: 1988)

Bhuwan Lal Joshi & Leo Rose, Nepal: Strategy for Survival (University of California Press, 1971)

Laurence Oliphant, A Journey to Katmandu with the Camp of Jung Bahadoor (John Murray: 1852)

Perceval Landon, Nepal, Volumes I and II (Constable: 1928)

Kanchanmoy Mozumdar, Nepal and the Indian Nationalist Movement (Firma KL Mukhopadhyay: 1975)

Mozumdar, Political relations between India and Nepal, 1877-1923 (Munshiram Manoharlal: 1973)

Pudma Jung Bahadur Rana, Life of Maharaja Sir Jung Bahadur of Nepal (Pioneer Press: 1909)

Cover photo: “Durbar group. King of Nepal, Col Ramsay the Resident, Rag Gooroo &c” by Clarence Comyn Taylor, 1863. Photo credit: British Library

1805

If the map for 1795 fairly represents the political state of India before the arrival of Wellesley [later Lord Wellington], this one shows the country after the administration of that distinguished statesman (1798-1805).

Commentary continued below

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Related material

No comments:

Post a Comment