Captions clockwise from top-left:

Captions clockwise from top-left:

The Empire's Salt Tax: Uncovering the Forgotten Hedge of India

The Great Hedge of India, also known as the Indian Salt Hedge,

was a particularly insidious project. It supported the Indian Salt Tax,

perhaps the cruellest form of extraction in the British Empire, which

levied excessive taxes on the essential commodity. The tax propped up

the British colonial project, while exacerbating state-sponsored

famines, killing millions and sickening millions more not only by

starvation but also by salt deprivation.1 Sir John Strachey, a British civil servant quoted in a footnote to Major-General Sir W. H. Sleeman’s Rambles and Recollections of an Indian Official, offers an account of the Hedge:

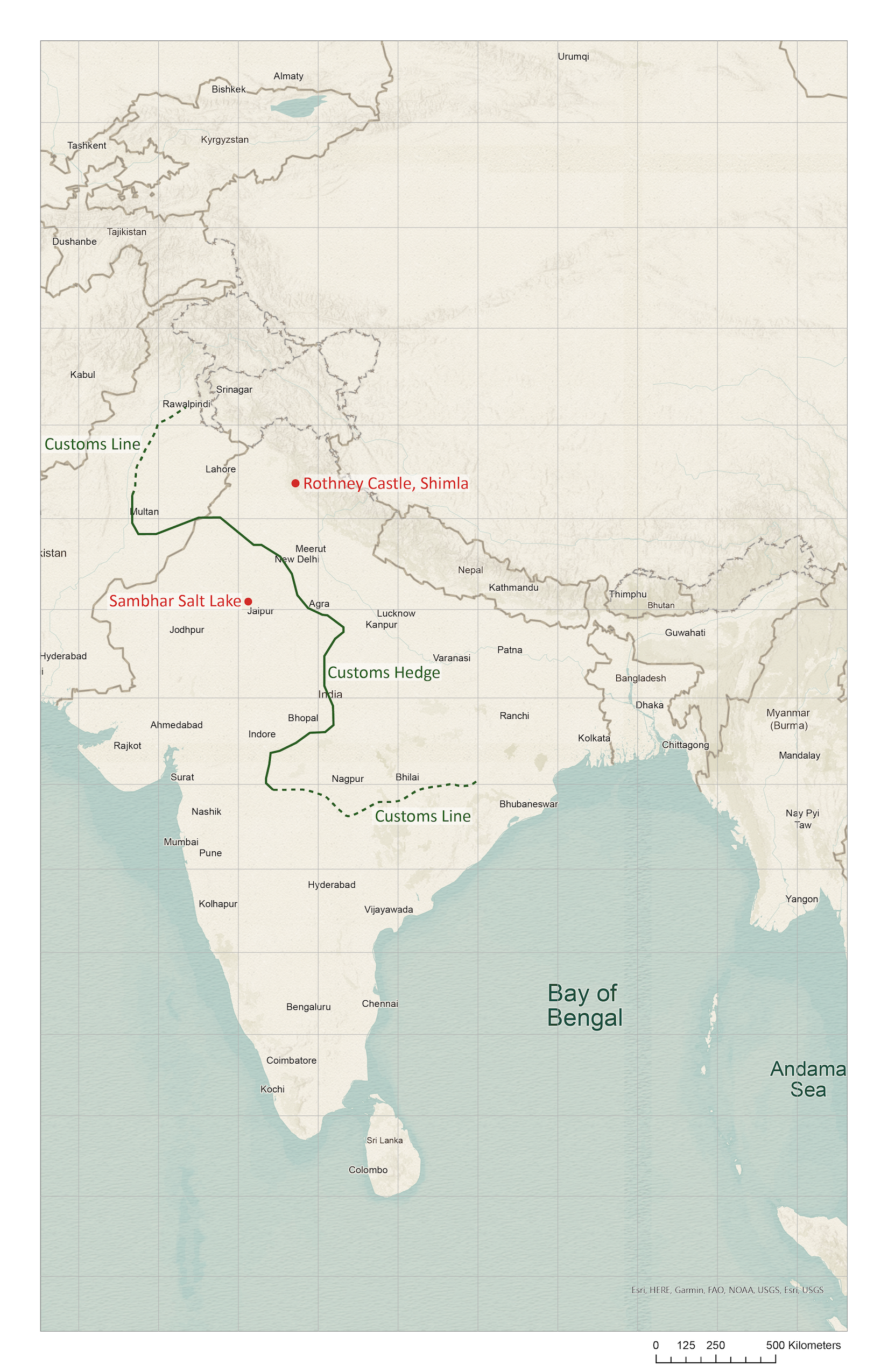

To secure the levy of a duty on salt… there grew up gradually a monstrous system, to which it would be almost impossible to find a parallel in any tolerably civilized country. A Customs line was established which stretched across the whole of India, which in 1869 extended from the Indus to the Mahanadi in Madras, a distance of 2,300 miles; and it was guarded by nearly 12,000 men… It would have stretched from London to Constantinople… It consisted principally of an immense impenetrable hedge of thorny trees and bushes.2

The Great Hedge of India was a vegetated, physical manifestation

of this “monstrous system,” explicitly designed to sow divisions and

extract resources. As it was eventually cleared from the landscape, it

also disappeared from people’s memories.

Although the Indian subcontinent has always had enough salt to support its needs via trade, large parts of the population live too far from sources of salt to make their own.3 The British exploited these geographic differences by heavily taxing salt in the areas they controlled. Under the governance of the East India Company, the British sought to build a physical barrier to stop desperate residents from smuggling cheaper salt in from other places like the Sambhar Salt Lake, in present-day Rajasthan.4 The Great Hedge of India was thus established in the 1840s as a form of deterrence and control, part of the Inland Customs Line, which divided the Indian subcontinent until the British assumed unified control over its disparate regions.5 The Customs Line surrounded the Bengal Presidency, the early seat of the British Empire in India, to tax all the salt that entered the region and all the sugar and salt that left it.6

Excluding a few stone walls where ground conditions constrained planting, the 2,504-mile-long Hedge was composed entirely of living vegetation.7 At its peak from 1869 to 1879, it stretched from the foothills of the Himalayas to the Orissa coast across parts of modern-day Pakistan and India.8 The Hedge was described as “utterly impassable to man or beast” and was heavily guarded by thousands of officers stationed at chowkies (guard posts) before it was abandoned on April 1, 1879.9 Made up of trees and shrubs chosen specifically for their impenetrability, it was a true feat of landscape design supported by incredible amounts of underpaid labour.10

For nearly half the nineteenth century, the Hedge attracted legions of British civil servants, labourers, and security guards. There is little information about who had the original idea of building a hedge across India, but historical records show that Allan Octavian Hume, a former commissioner of Inland Customs, played an outsize role in strengthening it. The Great Hedge not only impacted its immediate surroundings and those who lived there but also had far-reaching effects. However, despite the vast size of this living infrastructure and the violence it enacted, its existence quickly disappeared from historical memory, erasing the real stories of the people and landscapes it affected.

What little information is available about the Hedge is due to Roy Moxham’s seminal 2001 book The Great Hedge of India: The Search for the Living Barrier That Divided a People. Moxham’s book uncovered the existence of the forgotten Hedge and transferred its fragmented oral histories and written reports into a combined history and travelogue.11 In 1997, Moxham found a map of the Agra District at the Royal Geographical Society in Kensington Gore dated April 1879, when the Customs Line was abandoned.12 This map provided him with definitive proof of the existence and location of the project, and it remains the clearest representation of the Hedge given the lack of academic research on the subject. Contemporary researchers are now building off of Moxham’s work: Aisling M O’Carroll’s ongoing research project “Tracing the Great Salt Hedge” not only searches for the physical remnants of the Hedge but also considers its larger-scale territorial impacts;13 the journalist Kamala Thiagarajan’s article, “The Mysterious Disappearance of the World’s Longest Shrubbery,” rehashes Moxham’s work for readers of BBC's “Lost Index” series.14 However, the scarcity of sources documenting the Hedge and its impacts is a reminder of how the colonial state enacted violence by controlling written chronicles of its reign in a society that traditionally relied on oral histories to communicate with future generations.

The Hedge’s erasure from historical narratives about the British Raj belies its scale and influence on the Empire and the horrors it wrought, raising questions about how quickly people forget the events that have shaped their present. The omission of such histories thus reproduces the violence of colonialism by denying access to past knowledge that continues to haunt the present. Moxham’s work is pivotal, and remains the only major source of research on the Hedge. Its singularity invites further critical research to help expand and refine the stakes of the subject. This essay illuminates the story of the Great Hedge of India, which helped fill the coffers of the British Empire with salt taxes, by examining its intertwined landscapes.15 Tracing the Hedge and its legacy through two sites, the Sambhar Lake and Rothney Castle, with the help of Moxham’s work, will hopefully render visible the scope of its destruction and underline how critical the preservation of this history is to understanding how natural environments continue to be weaponized.

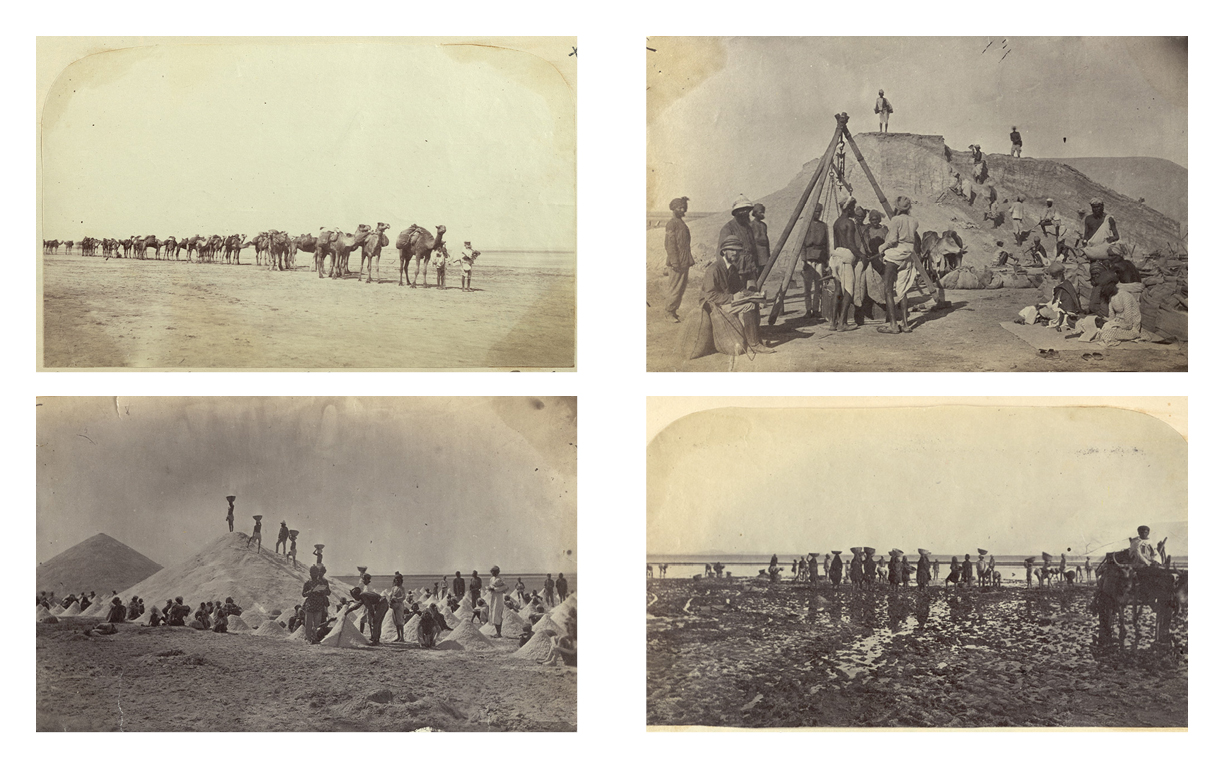

A major source of the salt that crossed the Hedge was the

Sambhar Salt Lake in Rajasthan, which has provided the mineral to the

subcontinent for centuries. In the dry season, water evaporates from the

lake, leaving behind salt sheets that are harvested and exported. The

inland saline lake is also a critical biodiversity zone—host to many

migratory birds, including flamingos.16

It is now gravely threatened because of pollution, land-use change, and

climate change. Nonetheless, it remains an exceptionally important

cultural and inancial resource, and an environmentally sensitive

habitat.

The various myths surrounding the Sambhar Salt Lake’s creation highlight its historicity and importance. In a popular story, the goddess Shakambhari Devi gifted a regional king a large tract of land covered in silver. The king requested that the goddess replace the silver with salt, a more precious commodity, leading to the creation of the 230-square-kilometre salt lake, which still has a temple dedicated to Shakambhari Devi on its shore.17 In more easily verifiable historical accounts, the Mughals extracted salt from the lake for the entirety of their rule, starting with Babur in the early sixteenth century, before handing it over to the rulers of Jaipur and Jodhpur around the mid-nineteenth century.18 On May 1, 1871, the British forcibly took over the saltworks at the lake, gaining control of “the principal source of salt going into the Bengal Presidency from outside the Customs Line.”19 Seven years later, A. O. Hume helped transfer all salt rights from the Princely States of Rajasthan to the British Empire by paying the rulers a nominal sum of money, a process presumably accelerated by imperial threats of property seizure and the takeover of kingdoms.20

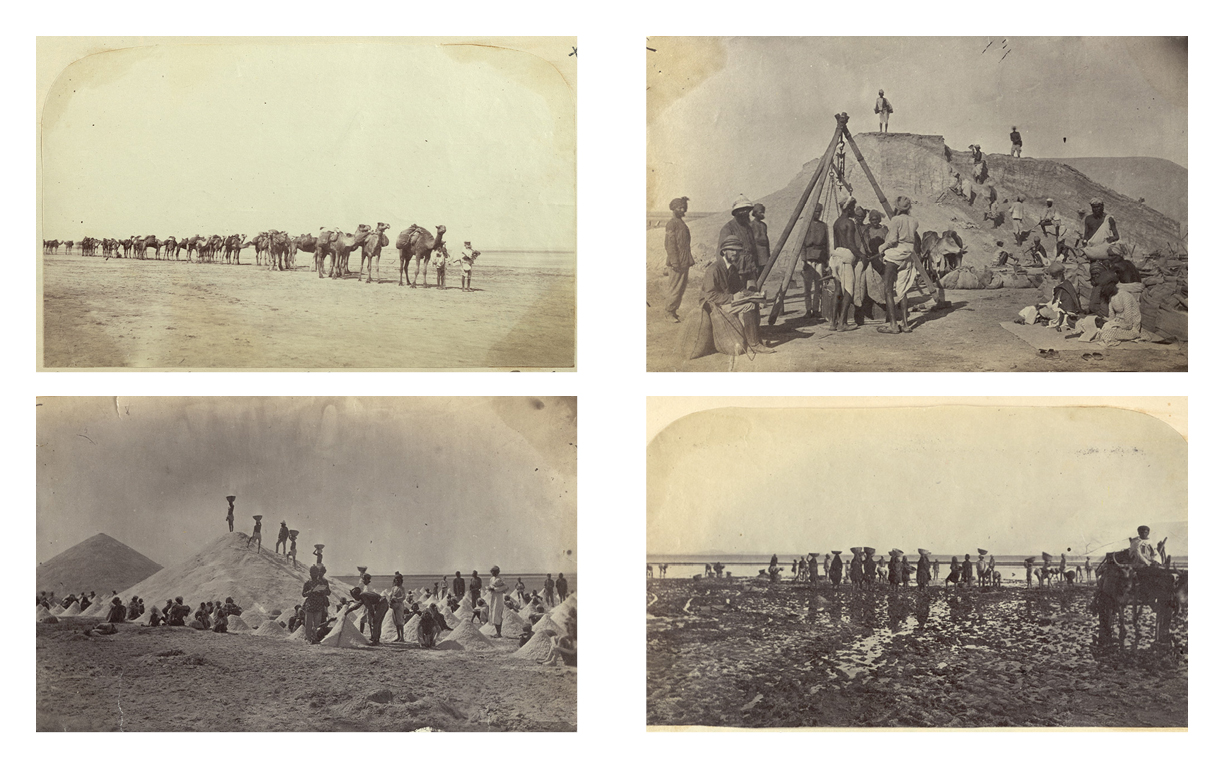

With the seizure of the Sambhar Lake saltworks, the British refined their tactics for controlling those engaged in the harvesting of salt. Historical photographs taken in the 1870s housed at the British Library’s archives show Indian salt workers, or malangis, labouring under the gaze of British overseers.21 Moxham writes about the plight of malangis not only in Sambhar but also in other salt-producing regions of the country, like the rock salt mines in Punjab and the coasts.22 Starting in the 1770s, salt workers, who often belonged to families of independent salt-makers, “had suddenly found their business expropriated, and been forced to work for pitiful wages” under the new system of contracts and leases.23 Although stories about their exploitation outraged members of the British public, the backlash was clearly not enough to ensure the malangis and their descendants greater dignity of labour—even in independent India.24 The salt that the malangis produced for those pitiful wages would have to cross the Great Hedge of India to be heavily taxed and sold to British Indian subjects at highly exploitative rates. From the late eighteenth century to at least 1836, the salt tax was around a sixth of a rural labourer’s income; at its worst in 1823, it went up to six months’ wages.25 Furthermore, locals were subject to new methods of surveillance and exploitation. Customs officers were stationed at chowkies near saltworks to prevent salt from being smuggled out.26 The Empire incentivised the officers to abuse their positions by paying them a pittance, thus tacitly encouraging them to extort the locals.

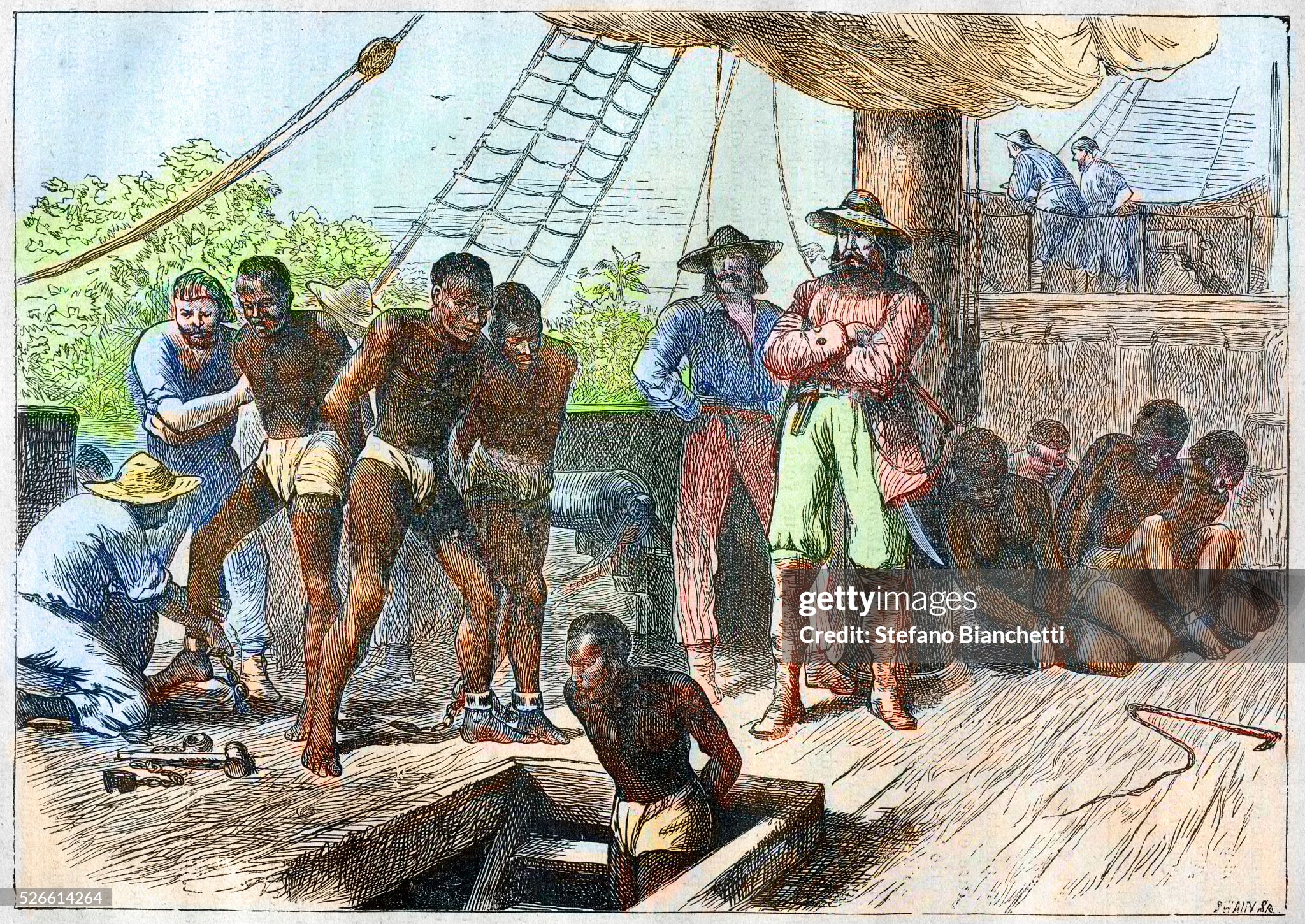

As a form of colonial wealth extraction built on slavery and

subjugation, the salt tax continues to affect national economies decades

after the sun finally set on the British Empire. Its profitability

encouraged the colonial state to invest enormous amounts of labour and

capital into the huge and destructive landscape design intervention that

was the Great Hedge of India. It is estimated that almost 14,000 people

worked for the Customs Line in 1869, though the labour of villagers who

planted the Hedge is not precisely documented.27

Even more work went into a previous iteration of the Hedge, which was

made up of dry shrubbery and required around 250 tons of material per

mile.28 According to Hume’s 1867−1868 report, dry hedges were destroyed by pests (like white ants), storms, fires, and natural decay.29

These failures encouraged the British administration to grow a live

hedge, an impenetrable barrier to keep an essential commodity from the

starving masses. As Hume pointed out in a subsequent 1869−1870 report, a

live hedge requires high labour inputs in its initial years but little

maintenance once it is established.30

Its existence was a point of pride for the British Empire. Hume

announced that the Hedge was to the Customs Line “what the Great Wall

once was to China, alike its greatest work and its chiefest safeguard.”31

Relentless attention to local vegetation and climatic conditions ensured that the Hedge thrived. In places where the land was incapable of supporting the Hedge, soil was imported. The use of a vegetated barrier perhaps served to visibly soften the brutality of the Customs Line in the public consciousness, but there was nothing benign about its design. Workers whose names have long been forgotten collected seeds from thorny indigenous plants that would grow fast and strong, selected for their ability to inflict maximum damage on those who tried to sneak across the barrier.32 The Hedge consisted of plant species like: babool (Acacia nilotica), Indian plum (Ziziphus mauritiana), karonda (Carissa carandas), nagphani (Opuntia, three species), thuer (Euphorbia, several species), thorny creeper (Guilandina bonduc), karira (Capparis decidua), and madar (Calotropis gigantea).33 Ridges were raised and trenches were dug to ensure both adequate drainage and rainwater collection.34 The resilience of live plants—or perhaps the maintenance that supported them—helped the Hedge endure environmental degradation.35 According to a commissioner of the Customs Line, the Hedge was “in its most perfect form… ten to fourteen feet in height, and six to twelve feet thick, composed of closely clipped thorny trees and shrubs.”36 It truly was an ecological marvel—though one designed to oppress.

After the Great Famine of 1876−1878, which killed 6.5 million people in British India,37 the British attempted to standardize salt taxes across the country, eliminating the market for smuggled salt and the need for a Customs Line.38 This was not born out of an altruistic desire to stop state-sponsored genocide—once the British controlled all of India, including the Princely States, the labour and money that went into maintaining the Hedge seemed wasteful.39 The Hedge was abandoned and gradually replaced by roads, housing, and farms—a stunning obliteration of such a carefully tended landscape feature. The natural forces that the British had fought so hard to keep at bay eventually took over, as did neighbouring landowners eager to expand their holding and government officials zealously building highways.40 Although some locals at the sites Moxham visited remembered that a hedge once existed there, the Hedge itself was largely lost to public memory until Moxham traced its path and found its remnants—a grassy line that gave way to a 40-foot-wide embankment covered in towering thorny shrubs before disappearing again—in Etawah, Uttar Pradesh.41 More recently, Aisling O’Carroll appears to have found a section of the Hedge in Palighar, and her research promises to uncover more knowledge of this forgotten landscape.42

The Hedge may have disappeared, but the wealth accrued by the

repressive salt taxes that it helped enforce, along with other colonial

spoils, continues to support the United Kingdom and many of its

intergenerationally wealthy citizens. One of the people who drew a

salary from the management of the Hedge was Hume.43

After a radical professional transformation, in which he went from

being a member of the colonial administration to helping found the

Indian National Congress to advocate for Indian independence, Hume was

forced out of the British civil services and bought an estate called

Rothney Castle in Shimla. He spent freely from his personal funds to

make Rothney Castle, with its sprawling grounds, “the most magnificent

building in Shimla.”44

A longtime enthusiast of nature in the nineteenth-century sense (more

interested in taxidermy than preserving live animals in their habitat),

Hume had used his horticultural knowledge to strengthen the Hedge,

growing it to near perfection.45

Given this expertise, he undoubtedly played a significant role in the

castle’s design, expansion, and upkeep—no small feat for an estate

spread over 17,500 square meters in mountainous terrain. He slaughtered

thousands of birds during his time as commissioner—many of which he

undoubtedly killed along the Hedge—and gifted 63,000 dead birds and

15,500 eggs to the Natural History Museum in London.46

Long after his exploits along the Hedge, Hume displayed parts of his

collection at Rothney Castle, where he lived for a few years before

returning to England to retire.47

Despite his support for Indian independence, Hume’s relationship to Rothney Castle in many ways reflects the ecologically and socially extractive practices of colonial governance that were bound up in the Great Hedge. Landscapes have long been altered in the Indian subcontinent, but the British sought to control nature to an obsessive degree. Hume’s work illustrates the jarring disconnect between the colonial fascination with the natural world and the violence unleashed to express “appreciation” for it. Hume slaughtered thousands of birds in what he saw as enthusiasm for avian fauna. Similarly, he used his extensive horticultural knowledge to drive millions of people to starvation instead of wielding it to restore landscapes ravaged by his government or support greater food security for a famished populace.Most importantly, Hume was able to leave India to return to England in 1894, while the millions of people affected by his and his administration’s policies had no choice but to deal with the repercussions. After his departure, Rothney Castle passed through various private owners, none of whom maintained it as well as its most famous inhabitant. Today, Rothney Castle lies overgrown and abandoned, an apt metaphor for the Hedge that funded its former glory.48

The Great Hedge of India has been destroyed and largely

forgotten by the descendants of those it oppressed. However, the fortune

the British Empire raised through its salt tax, extracted from the

blood of its subjects, persists via intergenerational wealth transfer

and money held by both the State and the Crown. The colonial regime had

obvious reasons to obscure its harshest cruelties in British India,

choosing instead to amplify its meagre claims of civilising hordes of

natives. What seems more shocking is that memories of the Hedge appear

to have been wiped out of contemporary Indian accounts of colonisation.

It is simply not mentioned in history books or referenced in discussions

about the Salt Tax.

Landscapes, as Simon Schama explains in his book Landscape and Memory, are inextricably linked to human recollections.49 “Before it can ever be a repose for the senses, landscape is the work of the mind. Its scenery is built up as much from strata of memory as from layers of rocks,” he writes.50 In the case of the Hedge, multiple generations forgot a visible landscape feature and the trauma it unleashed on the people it was designed to oppress. Even in a culture built around oral traditions, the Hedge’s disappearance is surprising; its omission (perhaps deliberate) from British colonial histories is even more jarring given the Empire’s obsession with documenting the minutiae of its reign.

The disappearance—both cultural and physical—is testimony to the

brevity of human memories and the transient nature of landscapes. It is

also a warning to us as we contend with shifting baselines in the face

of the climate crisis. Our histories are tied to the landscapes we

inhabit. It has become clear that our futures are also affected by our

past and present landscape manipulations. The cycles of destruction and

decay that swept away the Hedge and its associated landscapes seem more

predictable than our collective inability to comprehend the potential

horrors of the ostensibly innocuous profession of landscape design.

Those of us who work with the built and natural environments must be

attentive to landscape histories and cognisant of the violence that

landscapes can inflict. The Hedge created a diverse and vibrant

ecosystem, a stated goal of ecologists and landscape architects today.

It also starved millions and ranks amongst the cruellest human-made

structures in history. Unless we grapple with the power structures that

helped create and sustain the Hedge and the collective amnesia that

absolved its architects of responsibility for its excesses, we are

doomed to continue greenwashing borders and enclosures. The Greatest

Living Wall in history is dead. Where will it be raised next?

For more on how the British Empire utilized famine to entreAcknowledgement: A version of this essay was originally written for “Theories of Landscape as Urbanism,” taught at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design in Fall 2021 by Professor Charles Waldheim and Teaching Fellow Hanan Kataw.